With news last week of the New York Times and Washington Post being hacked recently, The Muckraker?s?Lyra McKee?looks at internet security.

?They were able to hack into the computer and remotely access my Facebook account, printing out a transcript of a private conversation. Then they told me who I?d been talking to over the past week and who was on my contacts list. They?d hacked into my phone. When they first told me they could hack into computers and phones, I didn?t believe them. So they showed me.?

I was sitting at the kitchen table of one of Northern Ireland?s few investigative journalists. He was shaken.

In thirty years of reporting, Colin (not his real name) has seen things that would leave the average person traumatized. A confidante of IRA terrorists, he has shaken hands with assassins and invited them into his home for a chat over a cup of tea ? as he had done with me that night.

A few weeks previous, during one visit from a source, the subject of hacking had come up.

?The day they visited me, they came straight to my home. I should have been in work but I wasn?t well. They didn?t even need to ring my workplace to find this out. Somehow, they knew where I was and came directly.?

Security has always been a worry for journalists in Northern Ireland. For investigative reporters here, life is a constant battle with those who want to silence us and have the means to do so.

Some have been murdered or attacked: in 2001, Marty O?Hagan, a newspaper crime reporter, was hit by a hail of bullets from loyalist terrorists as he walked home after a night out with his wife.

As of September 2011 the Sunday World, O?Hagan?s employer, had received 50 threats against its journalists, with one terrorism group planning to send a parcel bomb to their newsroom.

Other reporters claim they?ve been placed under surveillance: one colleague recently discovered a listening device in his home. Paramilitaries are not the only enemy; the security forces are said to monitor journalists like Colin, people they know to have regular contact with dissident terrorist groups like the new IRA.

With the spread of Internet use, monitoring journalists and their sources has become easier and more efficient, as I was to find out. What was an innocent visit to a fellow reporter?s home turned in to a journey inside the murky world of cyber surveillance, a world in which a reporter?s sources are never safe.

How could I talk to my sources securely?

I had one question: How could I talk to my sources securely?

Email was my main means of communicating with them. It?s less intrusive than a phone call. They can reply in their own time, away from the prying eyes of employers and colleagues.

In a conversation with other journalists, someone suggested using Hushmail. Hushmail is a web-based email service that encrypts email communications so that only the sender and the intended recipient can read it, using proprietary technology called the Hush Encryption Engine.

It is perceived to be more secure than Gmail yet few reporters have questioned how the technology behind it functions.

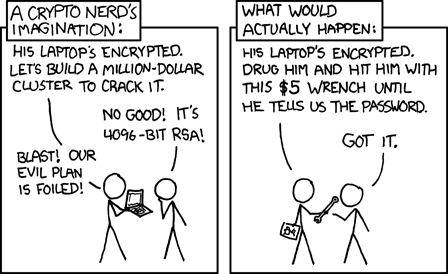

That?s a key problem for journalists trying to improve their digital security. Many journalists are technophobes and place blind trust in services like Hushmail to protect them and their sources ? without questioning their credentials. The word ?encryption? itself has an onomatopoeic quality, suggesting something ?unbreakable? or ?sealed?. That is incorrect.

Let?s look at what encryption actually is. Very simply, when an email message leaves your inbox, it?s rendered unreadable until it reaches its intended target: the recipient.

Only someone with password access to the recipient?s email account can read it. Or someone who can decode the decryption.

As Paddy Foran (@paddyforan), a New York-based developer specializing in server-side technologies, points out, encryption is not bulletproof from penetration by hackers.

?All encryption is breakable, given enough time and resources. It has to be or it?s useless: the system has to be able to decode the message for the recipient to read it, after all.?

With the use of a supercomputer, Paddy argues, a government department could decode high-level encryption within ?weeks, years or months.?

The encryption is locked by random combinations of numbers, known as ?keys?. A government supercomputer will generate billions of random combinations of numbers until it finds the combination that matches the keys and unlocks the encryption, making the messages readable.

Foran explains it in simpler terms:

?It?s as if I said ?I?m thinking of a number between one and a billion. If you guess the number, I?ll tell you what the message said.? The computer is trying to guess the number.?

In short, encryption is not infallible. Services like Hushmail protect users from malicious hackers with limited resources but if a government department ? an investigative reporter?s likely enemy ? wants to know who your sources are, they will be able to find out.

And they don?t need to hack your account to obtain this information. In 2007, Wired.com?s Threat Level blog revealed that Hushmail regularly complies with government court orders demanding users? emails.

The government in question has to apply for a formal order through the Canadian courts first but ultimately Hushmail will not fight their demands.

In one case the company handed over ?12 CDs? worth of emails from three Hushmail accounts.? What?s more, users are rarely notified that a court order demanding their information has been made (or if it has been successful). By email, Hushmail?s Support Manager Chris Fraser said:

?Because such orders generally state that we are not permitted to disclose the existence of the order to a user, we will not disclose to any user the existence, or nonexistence, of any order we may have received.?

This is a problem journalists will encounter with nearly every app they use to store their information: companies will comply with court orders demanding your data ? without your knowledge.

In a 2011 Transparency report, Google wrote that of the 1,425 user data requests it received in the United Kingdom, it complied fully or partially with 64% of them.

In the United States, this figure shoots up to 90%.

The biggest issue for a journalist?s digital security is not a hacker?s ability to guess their password but the government?s ability to obtain their data through legal wrangling.

?Digital gurus?

?Are there any services that won?t comply with the government and the courts??

I was talking to a group of hackers online. As a journalist with little technical knowledge, these guys are my ?digital gurus?: technical geniuses, some of whom have been poached by the Ministry of Defence to work on projects.

They are paranoid about their online security in a way that only people who make a living cracking passwords can be.

The answers I received were disheartening. The only option, they argued, was to self-host my data, files and email on a server.

Even then, the server would be rented from a third-party provider like Amazon EC2, a provider that could be subjected to and made to comply with the same court orders as any other.

The next option I explored was using open-source tools developed by hackers to ?stay anonymous?, like TrueCrypt, Retroshare and Tor.

These tools were developed specifically to protect users from the prying eyes of ?Big Brother? ? governments and other institutions ? meaning there is no risk of them complying with court orders demanding a user?s data:

- TrueCrypt is a desktop app that creates a virtual encrypted disk that you can store files on. It also allows you to create a secret volume within the disk where you can store extremely sensitive files. So if you?re ever forced to reveal your TrueCrypt password (for example, by court order) the sensitive files you?ve stored will remain hidden because no one will know about the existence of the hidden volume. You?ll only need to reveal the password for the ?public? volume.

- Retroshare is a free desktop app that allows you to share files and chat with your friends over IM. To share files with your friends, you must first exchange PGP certificates; the transfer itself is encrypted using OpenSSL.

- Tor is a browser that allows you to browse the Internet anonymously, preventing anyone spying on your network from learning what sites you?ve visited. However, services like Gmail will still record when you?ve accessed your account, allowing someone monitoring your network to build up a picture of your online activity regardless.

Dan Porter, a Belfast-based security consultant, says?TrueCrypt implements good encryption and offers a ?great level of security? whilst still being simple to use. However, he adds:

?Like any encryption software, the security relies on good choice of passphrases/keys etc.

?The other issue is hiding your encrypted data. Depending on how secure you want it, it?s sometimes best to make it look like there?s no data at all [through the use of the hidden volume feature in TrueCrypt]. You could be forced to decrypt it and charged with holding evidence if you don?t do it so plausible deniability creates a scenario where it?s impossible for them to prove you have data encrypted there in the first place.?

According to Dan, security breaches in data are usually little to do with apps like TrueCrypt. Instead, they?re normally caused by the carelessness of the user.

?Here?s a simple scenario: you could have a TrueCrypt volume, protecting some data you don?t want others to see. If it was me, I wouldn?t store it on my laptop but rather a separate drive in a different location, hidden inside an old hard drive backup, in a file you would never guess was a TrueCrypt volume.

?This is already a good level of security ? the likelihood of someone finding this is very small.

?However, accessing this from my Mac, mounting it and entering the passphrase gives access to it on this machine I?m typing on.

?If there are pictures or documents within the encrypted partition, and you view one on your machine, the data moves from the encrypted device to your machine in order for you to view it.

?My Mac isn?t encrypted. So, if my Mac keeps a cache of files, the image may remain on my machine for an unknown amount of time, in an unknown location.?

At the end of our interview Dan summed his thoughts up thus: ?My lesson is simple ? it?s more important to hide your data than encrypt it because passwords are easier to guess than hiding places.?

4 final tips

As I noted earlier, most journalists do not understand technology. Having an iPhone does not mean you know how it works ? not in a way that the programmer who built it does. Relying on something you don?t understand to protect your sources is a big risk.

So what can you do to improve your security and protect your sources? Below are a few tips. These may sound like something you?d read in the MI5 manual for spies but if sources are risking their livelihoods and their lives to talk to you, you have a duty to protect them.

1) ?Assume that someone, somewhere can hack into your computer

With that knowledge, you won?t take any unnecessary risks by storing sensitive information online. A hacker cannot hack into your notebook.

I keep meticulous notes of research on my computer but I use codenames for sensitive sources.

A police search of my home would not surface information that could identify those sources either.

2) Use ?burner? emails

You?re familiar with ?burner? phones, right? In spy movies, the protagonist buys a phone and disposes of it when it?s done so it can?t be tapped or traced.

Burner emails are much the same. Create an email account under a fake name for the purpose of communicating with a sensitive source.

Don?t access the email from your personal computer. Even using a public computer in a library on the other side of town will work; as long as you?re not a member of the library, no one can connect the address to you.

Print copies of the emails and when you?ve moved on to another story, destroy the address.

Advise your source to create a fake email address and agree on a codename (for example, ?John Bryans?).? So if your source should need to contact you again, John Bryans will email your regular address.

3) School your sources on digital security

As a journalist, our sources are our responsibility. It?s our job to school our sources on how to contact us securely: for example, by contacting from a fake email address via a computer that can?t be connected to them.

4) Prepaid phones and SIMs

Buy a cheap handset for ?10 or ?20. Dispose of it every four weeks, communicating your new number to sources face to face if you can.

If nothing else, you?ll make life hell for the person trying to monitor your phone calls.

Disclosure: Lyra McKee is a distance learning student on the MA in Online Journalism at Birmingham City University.?

octomom dan savage new world trade center kellen moore ryan braun bryce harper may day

No comments:

Post a Comment